The first thing you see when you walk into Nightingale Bread, which opened at the beginning of May, is the mill that grinds grain into flour. The 1,000-pound pink granite mill sits in a circular chamber, built just for this purpose.

Like its neighbors at Lincoln Center, Building3 Coffee Roasters and Café Red Point, Nightingale is a former elementary school classroom. Hints of this former life still exist in the black tile trim — old chalkboards — as well as Nightingale’s emphasis on educating customers on its product.

In fact, owner David McInnis has put the entire process on display, starting with the mill, which he imported from Raleigh, North Carolina himself.

“For us, the process starts with the grain,” McInnis says of his raw materials, sourced from small farms.

Once the grain is ground down to flour, he then mixes up the dough by hand in a large wooden French trough. He’s also utilized the exterior windows for passersby to view the process of mixing the bread and then forming the dough.

McInnis wasn’t sure the French trough would make it when we first spoke in January. “It might honestly be kinda dumb,” he said. Hand mixing obviously takes a lot more time and effort than its industrial counterpart, but McInnis wanted to give it a shot. With bread-making, he says, “You’re teaching your hands how to think.”

McInnis wasn’t sure the French trough would make it when we first spoke in January. “It might honestly be kinda dumb,” he said. Hand mixing obviously takes a lot more time and effort than its industrial counterpart, but McInnis wanted to give it a shot. With bread-making, he says, “You’re teaching your hands how to think.”

In our recent visit though, he’s found it more practical than he thought, and it’s officially part of the process.

From there, the dough rises for a few hours, is shaped, and then set aside in a cold storage room to ferment overnight. It’s then baked in a five-tier Italian bread oven.

Even the dish pit got some love. Positioned front and center next to the mill chamber, it too got the black and red tile trim. McInnis’ take: Why should the dining room be beautiful but the kitchen ugly? And it’s not just for the employees, but for guests too. “You see more of the whole process,” he says, adding, “It’s not just a quality thing, but a quality of life thing.”

McInnis, who is originally from New York, began an interest in bread after working on a vineyard in the Finger Lakes region. He learned it was mostly about putting in the work, and he liked that. From the winery he made his way over to Wide Awake Bakery, where he worked for three years. (You can watch a video of Wide Awake’s process, which is somewhat similar to Nightingale’s, here.)

McInnis settled in Colorado Springs two years ago. Much of his time since then has gone into building Nightingale, the majority of which he’s done himself. “It’s been like going to business school and trade school,” he says with a laugh.

McInnis settled in Colorado Springs two years ago. Much of his time since then has gone into building Nightingale, the majority of which he’s done himself. “It’s been like going to business school and trade school,” he says with a laugh.

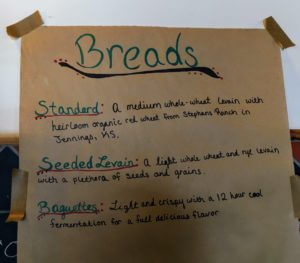

Don’t expect a static menu from Nightingale, what looks good at the market that day, or what McInnis is feeling is what you’ll find on the shelves. (At least for now, watch online for a regular menu later this summer.) One caveat so far is pizza day, set aside for Saturdays from noon to 2 p.m. He’s also planning on a breakfast table, in which he’ll stock a table with breads, jams, butter and fruit for an informal meal.

At its core, however, Nightingale is about the bread itself. It’s all naturally leavened with whole grains, but McInnis doesn’t want to see his loaves as just healthy, or just artisan, options. He shies away from the terms altogether.

“All I wanna do … I just want to make normal bread,” he says. “I just want to make something that people would have traditionally called normal bread.”

Though normal hardly seems fair, given the gorgeous, toasty flavor of the loaves, and the way they — while quite hearty — don’t settle heavy in your stomach.

McInnis likes that the bar for bread appreciation is low, unlike, say, wine. It’s humble, and easy to enjoy. As he puts it: “There’s no ‘I don’t get this.’”

Getting back to the grain, and focusing on crafting instead of assembly, lies at the core of what McInnis is planning for the menu.

“It’s like coffee,” he says, “if you can get people excited about drinking black coffee … then you don’t have to mask it.”

“It’s like coffee,” he says, “if you can get people excited about drinking black coffee … then you don’t have to mask it.”

While he’s open to adding goodies like goat cheese, raisins and olives to his loaves, he wants to keep the focus on the manipulations available on the ground floor, such as mixing grains. “There are a lot of variables [already],” he says. For example, rye grains change not only taste, but texture; the shape of the loaf itself changes a lot of the internal characteristics, like crust-to-crumb ratio.

As he puts it: “How can we get people excited about fermenting wheat?”

[Images: Edie Crawford]